Errors and Either

March 25, 2020

Welcome to yet another post on the Internet about Monads! I am only mostly

kidding. I do not intend to use this post as an introduction to

Monads1. This post is actually a continuation of my post on

errors, and I would like to dig into the practical upshots of

implementing more thorough and efficient means of handling errors.

Specifically I am picking up the sentiment that we can do better. Using

Either is one version of doing better that I’d like to consider in this

post.

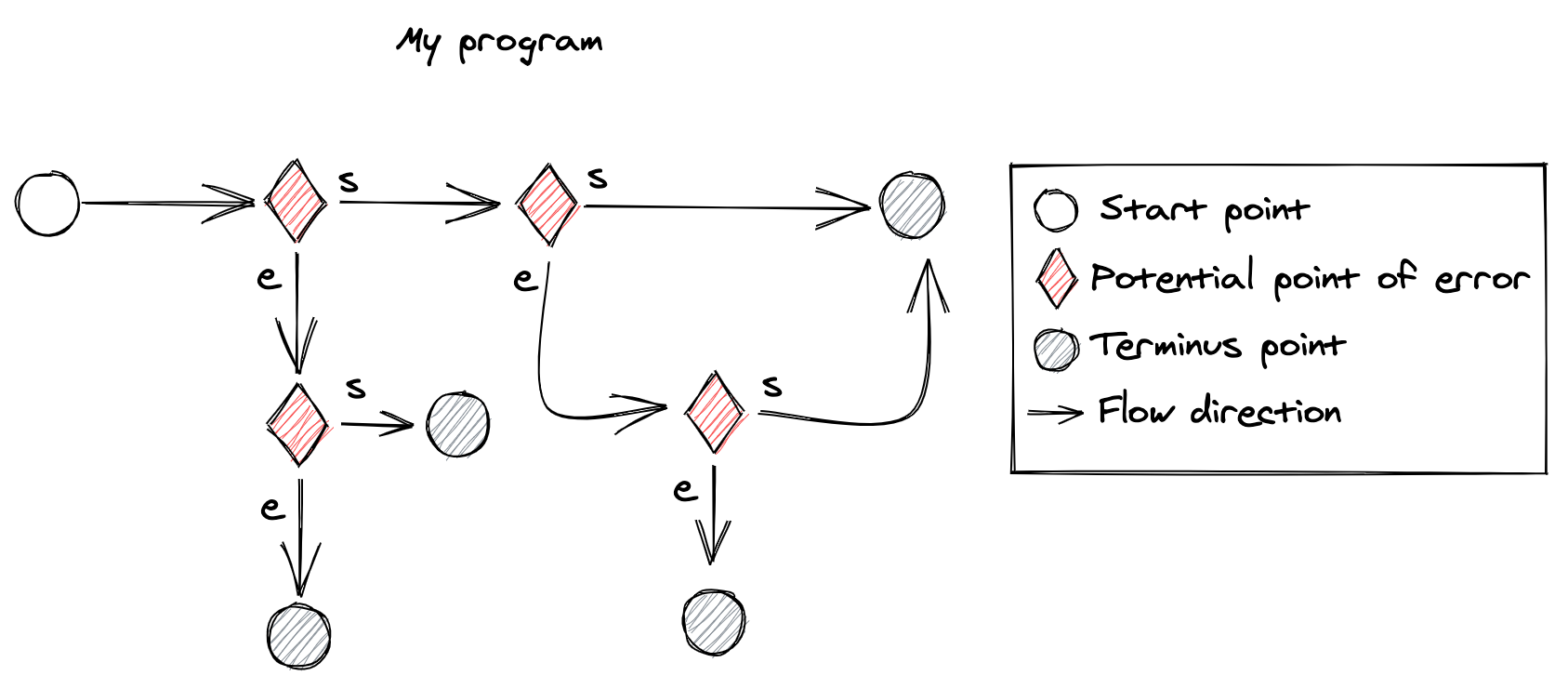

Consider the following diagram:

Figure 1 features elements of a typical program; a start point, branch

conditions and terminus points. Real programs could be expressed as sets of

these diagrams linked together, one’s output the input of the next. Our

branching here is focused on errors. Each diamond is a point at which we take

an action that could result in an error condition. The s branch indicates

a successful result where the e branch indicates an unsuccessful result.

This is the error control flow inherent in any program that could have

error conditions.

The different terminus nodes indicate different end states that our program can reach. Each end state indicates a different type of output. This toy program has four different potential terminus states. Following this pattern we can imagine that if Figure 1 program grew to any level of complexity there would be explosion of terminus states as new points of error are introduced.

Moreover, think about what the terminus point represents the end of the programmers intent. It is saying “We have reached this point without generating the outcome we had hoped, so send a message back expressing this unexpected event”. These intentions exist implicitly or explicitly in our programs.

This may sound like an ungracious description of how many programs work, but practice is often not far off from this. Consider this JavaScript:

let locked = false;

const lockSomeResource = () => {

locked = true;

};

const unlockSomeResource = () => {

locked = false;

};

const doSomethingDangerous = () => {

throw new Error('You got burned!');

};

const resource = 'resource';

try {

const locked = lockSomeResource(resource);

doSomethingDangerous(locked);

} catch (e) {

console.error(e);

} finally {

unlockSomeResource(locked);

}This code is a representation of one of the diamonds in Figure 1.

Clearly we will reach the e branch. And log the error to the browser

console. But consider what might happen if unlocking the resource is a known

potential point of error too. To achieve our goal of improved error messages

we might make the following alterations:

let locked = false;

const lockSomeResource = () => {

locked = true;

};

const unlockSomeResource = () => {

throw new Error('Nope!');

};

const doSomethingCoolButDangerous = () => {

throw new Error('You got burned!');

};

const myFunction1 = resource => {

try {

const locked = lockSomeResource(resource);

return doSomethingCoolButDangerous(locked);

} catch (e) {

console.error(

`something went wrong with locking the resource or doing something dangerous, either way: ${e}`

);

return undefined;

} finally {

try {

unlockSomeResource(locked);

} catch (e) {

console.error(`could not unlock the resource because: ${e}`);

}

}

};

myFunction1('resource');The snippet above is a representation of a path in Figure 1 where

we reach two, successive error conditions. Nested try-catch blocks may seem

like overkill but they are the only way to ensure that our error states are

kept in check. We can continue to flesh out this example and perhaps refactor

our code so that each potentially dangerous call is inside of it’s own

try-catch block, we may even be tempted to provide a more generic way of

provisioning these try-catch-finally blocks for functions. Another point to notice here is that we have

assumed myFunction1 should return something to the caller. Either it is the

result of doSomethingCoolButDangerous or it is undefined

— returning undefined is our implicit way of communicating that something went wrong,

let’s say we made this part of our contract to calling code. This is how a

lot of programs operate. I would assert we can do better than this,

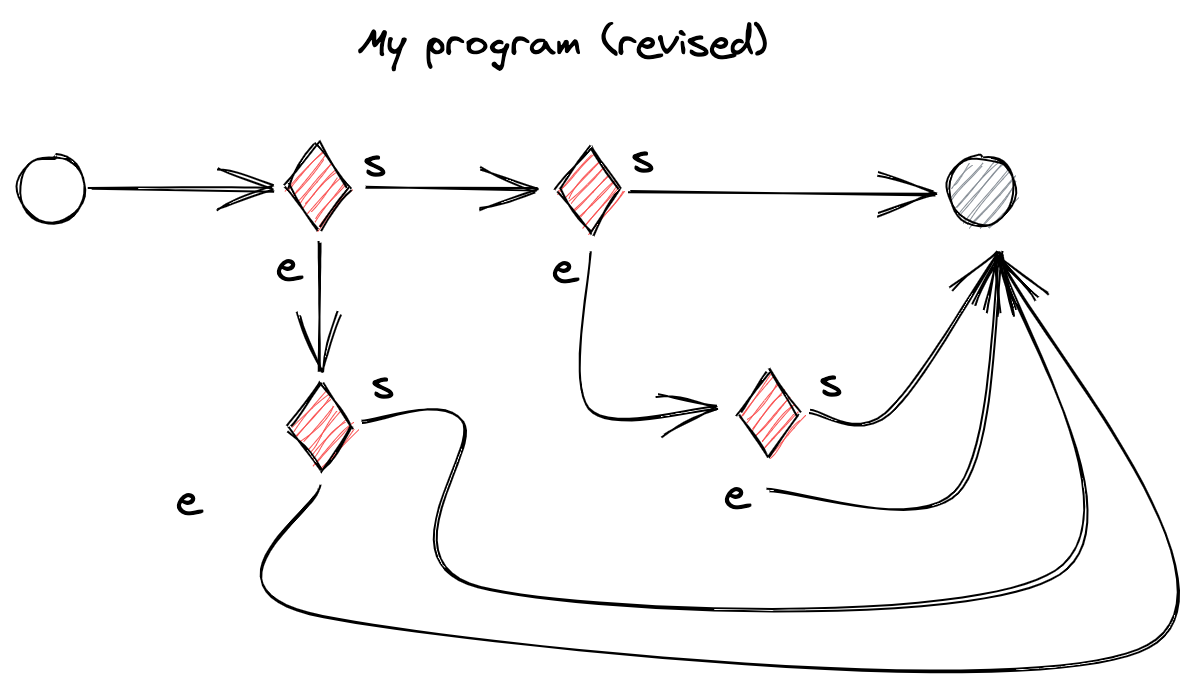

and write less code with less nesting. Consider this revision to our graph:

In the figure above we have eliminated all terminus points but one. In some sense

the diamonds have been made totally irrelevant to the output of our

program. I would like to demonstrate that this is what the Either monad

was made for. All paths lead to one output, no matter what happens. Either can be considered an abstract way

of expressing uncertainty in our programs and so it is a very general data

type2. The way Either makes this possible is by placing the

result of our function inside of a tagged container. It is this tagging

that lets subsequent code know whether some went right or wrong, in Either

terms; left or right. Left denotes a failure where right denotes a success.

By placing values inside of containers like this we are able to associate some

metadata with the a given output. Consider this example (in TypeScript):

const unsafeJSONParse: (unknownString: string) => object = JSON.parse;This function can easily represent one of the diamonds in our program where

an unknown string value can be passed in and one of two things will happen:

an error, or a newly minted object. Consider this revision with Either as

implemented by fp-ts:

import { tryCatch, Either } from 'fp-ts/lib/Either';

const jsonParse = (unknownString: string): Either<string, object> =>

tryCatch(() => JSON.parse(unknownString), (e: Error) => e.message);This is slightly more verbose for a start, but if we look at the return type

we are now returning an Either3! This change is most important

at a type level: we have now declared that jsonParse no longer produces

an object but Right<object> or Left<string>. The Right or Left

result of this function is what enables us to eliminate other terminus

points. Furthermore we can now more generically handle control flow

introduced by errors. There is no need to ever have a nested try-catch block

again. Returning to our example from before, we can refactor like so (still

using fp-ts, though specific fp-ts knowledge is not required):

import { pipe } from 'fp-ts/lib/pipeable';

import {

Either /* <- Type only */,

either,

left,

right,

isRight,

} from 'fp-ts/lib/Either';

let locked = false;

const lockSomeResource = (

eitherR: Either<string, any>

): Either<string, any> => {

if (isRight(eitherR)) {

locked = true;

return right({});

}

return left('oops!');

};

const unlockSomeResource = (

eitherR: Either<string, any>

): Either<string, void> =>

isRight(eitherR)

? left('Try to unlock the resource but we failed')

: left('Something upstream failed, we do not have a resource to unlock');

const doSomethingCoolButDangerous = (

eitherR: Either<string, any>

): Either<string, any> =>

isRight(eitherR) ? left('You got burned!') : left('You got burned!');

const myFunction1 = (resource: Either<string, any>) => {

return pipe(

lockSomeResource(resource),

doSomethingCoolButDangerous,

unlockSomeResource

);

};

myFunction1(either.of('resource'));Ok, that was an explosion of new code that looks very FP! You may be

wondering how on earth this is an improvement over the nested try-catch and

at this point it really is not. For instance, there seems to be more repeated

code, albeit not-nested. Also, what is this either.of? What is pipe even?

I would challenge the reader to not dig too deeply into those concepts but

rather to look at the body of myFunction1. What is being described there?

Take a moment to think about what the result of calling

myFunction1(either.of('resource')); might be.

Ok, it’s:

{ _tag: 'Left',

left:

'Something upstream failed, we do not have a resource to unlock' }Trace through the code and consider how we arrived at this result.

Consider that we still have a fairly imperative way of laying out

instructions. The primary change has been to separate steps into functions

and we now have the Either machinery so we don’t deal with values directly.

Instead, we interact with a container that has been tagged which

carries our value. In each of our functions we now accept Either and return

Either. At a type level we have achieved the simplification of our graph —

one terminus — but at the cost of developer experience and ergonomics.

Someone once told me that we don’t abstract something unless you have at least

three different instances of the same thing as a guiding rule. In the refactor above we

are repeatedly checking our code for isRight and then taking some action

based on that. We are wrestling with control flow at a lower level.

However, I would argue that this is a very similar algorithm to what we had

above except that each point of error has been exposed and is being handled!

The container itself is our signal for control flow through our program. Currently it is cumbersome and we can certainly do better — fortunately others have already noticed this; consider a further revision:

import {

either,

map,

mapLeft,

bimap,

chain,

tryCatch,

fold,

} from 'fp-ts/lib/Either';

import { identity } from 'fp-ts/lib/function';

import { pipe } from 'fp-ts/lib/pipeable';

let locked = false;

const lockSomeResource = (res: string): any => {

locked = true;

return {};

};

const unlockSomeResource = (res: any): void => {

throw new Error('Try to unlock the resource but we failed');

};

const doSomethingCoolButDangerous = (res: any): any => {

throw new Error('You got burned!');

};

const myFunction1 = (resource: string) => {

return pipe(

either.of(resource),

map(lockSomeResource),

mapLeft(() => {

console.log('this never runs!');

return {} as any;

}),

chain(res =>

tryCatch(

() => doSomethingCoolButDangerous(res),

(e: Error) => ({ e, res })

)

),

bimap(

({ e, res }) =>

tryCatch(

() => unlockSomeResource(res),

(_e: Error) => `Our final result, ${e.message} and ${_e.message}`

),

(res: any) =>

tryCatch(() => unlockSomeResource(res), () => 'Not our final result')

),

fold(identity, identity)

);

};

myFunction1('resource');We are now close to a final version and our original myFunction1 is

intact. Control flow is now happening at a higher level thanks to the

different functions (or operators) for working with data types. Technically there is still

some amount of “nesting” but we will never need to go deeper than this. There

are some more advanced operations being used on the container such as chain

and if you have checked out the linked resources you will be familiar with

what all these operators do4. This time our output looks like:

{ _tag: 'Left',

left:

'Our final result, You got burned! <and> Try to unlock the resource but we failed' }Hopefully this discussion has piqued your interest for digging deeper into how we might better handle errors in our code. There are, of course, different theses about using abstract data types to handle values in this way4. For now, thanks for reading!

Notes

- The Mostly adequate guide does an excellent job of getting hands on with Monads and I would highly recommend checking it out.

- See the fantasy land specification

for where Monads fit in with other general data types.

Maybeis a similar instance toEitherbut it uses different tags. - fp-ts already has an implementation of

jsonParsecalledparseJson, but I decided to implement one as it is a nice simple case for getting started. - I would challenge the reader to create handler called

alwaysthat takes a left or a right and runs the same function - This talk by Rich Hickey is quite a famous one that contains a lot of wisdom regarding some of the pitfalls of abstract data types.

Hi, I'm Jean-Louis Leysens. I like writing software in JavaScript and TypeScript and listening to noisey music.